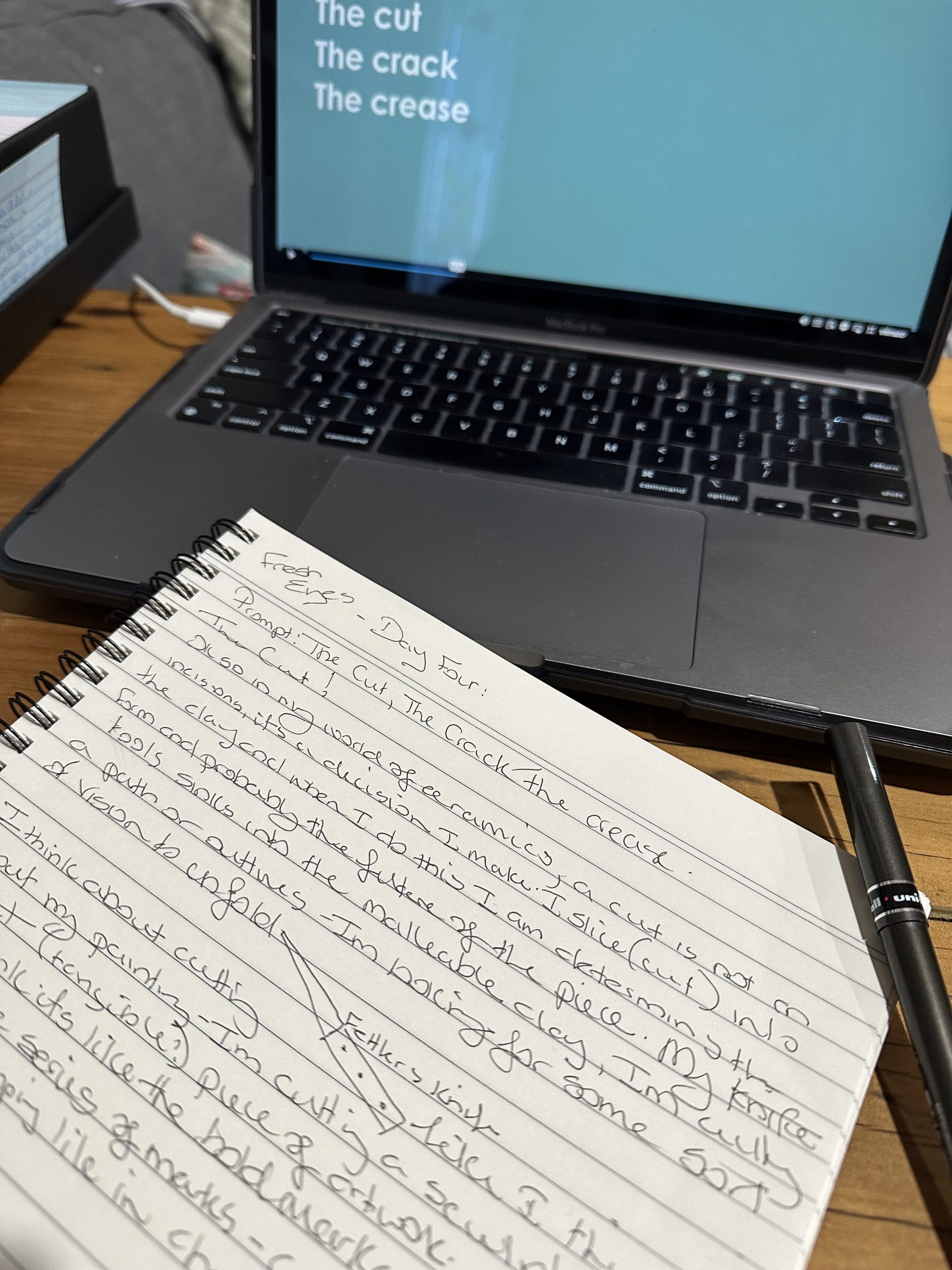

Day 4: The prompt: The Cut, The Crack, The Crease

Ok, so this is by far the best prompt yet. I immediately knew what I could write about this. The prompt reminded me of the first page in a book that I read by the author Bertie Blackman in her book Bohemian Negligence. It is about cracks. I read and re-read this page all the time. I stuck it up on my wall because the writing resonated with me in a profound way.

Check out my post on Bertie Blackman’s writing about cracks here

Here’s my take on The Cut, The Crack, The Crease, as writing prompts.

The Cut

In my world of ceramics, a cut is not just an incision; it’s a decision. With each slice into the clay, I determine the form and future of the piece. The tool moves through the malleable material, carving pathways and outlines, allowing for some sort of vision to unfold.

Much like in painting, the cut in the clay sculpts raw potential into tangible art. It’s the bold lines in one of my sketches, the deliberate marking of territory and mapping, guiding the subsequent layers and embellishments.

The Crack

The cracks in my vessels tell tales of transformation. From wet clay to hardened form, the journey of ceramic creation is fraught with tensions, of drying, of firing, of glazing. While some cracks are unintended, revealing the stresses of creation, others are purposefully integrated like the portals in my new “Arcadian Aperture” artworks.

Cracks can highlight my embrace of of imperfection, getting a bit Wabi Sabi is cool. In visual art, cracks can represent the passage of time, the fragility of existence, or the organic nature of life. Each crack, whether by accident or design, adds depth to the narrative, allowing my artworks to be a testament to its creation and to me as its maker.

The Crease

In the world of visual arts, a crease is a deliberate shadow, a play of light, a fold in perception. Clay can be creased. The concept is present in the way textures intersect, layers overlap, and forms bend. The crease becomes a tactile exploration, guiding my fingers and eyes, leading them on a sensory journey. It’s the ridge on a sculptural vase, the deliberate indentation that catches the glaze just so, or the fold in a paper substraight that adds a third dimension to a two-dimensional space. The crease is where predictability ends and surprise begins, and maybe it’s about my attempt to see beyond the flat surface.

The Cut – creatively written

The cut was deep, not of flesh but of spirit, carving through layers of experience, memory, and emotion. It was the kind of cut you don’t see but feel—a wound that leaves no blood, but seeps with sorrow. Yet, like all incisions, it also opened up space, a gap, a possibility. From this cut sprouted a new understanding, the growth of resilience. The cut became a portal to a world of introspection, a testament to the strength within wounds and the stories they narrate.

The Crack – as a flaw

Cracks are often perceived as flaws, imperfections marring a pristine surface. When I look closely, my cracks (in me) reveal a history of endurance. Each crack is a roadmap of challenges faced, of pressures weathered. My cracks show where breaking points were met, and sometimes, but not always, were succumbed to. Through the fissures, light penetrates, illuminating previously hidden truths and vulnerabilities. My cracks don’t signify weakness; they embody survival, proving that even when fractured, one can remain standing and maybe even taking small steps to keep moving forward.

The Crease – as a sign of care

A crease is both a mark of use and a sign of care. My mother taught me the latter as she guided me through my stereotypical conditioning as a female learning to iron the workshirts of my father and brothers when I was nine years old.

The crease indicates where hands have folded, purposefully shaped, and meticulously moulded. A crease in a page of my books denotes a place of return, a thought worth revisiting. In fabric, it shows intent, a deliberate design or perhaps a repeated motion. A crease is evidence of interaction, a quiet dialogue between material and maker. While some may strive for the sleekness of the unmarred, the crease tells of life lived, of purpose, and of the beauty found in thoughtful repetition. Despite the ‘training’ I received as a young girl in all the ways a woman should execute the tasks of a good housewife, I enjoy pressing, folding and creasing clothes in the same way I enjoy similiar actions with clay and paper.

End of Day 4

Recent Comments